The view from the Cuipo Tree: Rethinking Biodiversity Beyond Protected Areas

Biodiversity

Biodiversity is often discussed in abstract terms, percentages protected, species at risk, and hectares conserved. Ecological networks operated at vast and local spatial scales. It lives at the intersection of forests and farms, rivers and roads, protected areas and working landscapes.

Geospatial intelligence allows us to see these intersections clearly: to understand where species persist, where pressures emerge, and where small land use decisions have outsized ecological consequences.

I visited a harpy eagle nest today, one of the hardest birds to see. I saw the mother and chick nesting in a giant cuipo tree on the edge of a nature reserve in Panama’s Darién region.

The Darién Gap is a remote, dangerous, roadless jungle spanning the Panama-Colombia border, acting as a formidable natural barrier between Central and South America, infamous for its treacherous terrain, wildlife, and human threats. The dense rainforest, swamps, and mountains interrupt the Pan-American Highway. For the hundreds of thousands of migrants heading to North America, it is a perilous part of the passage; they may face fast-flowing rivers, criminals, and traffickers.

The Harpy Eagle’s nest was discovered by farmers who notified local bird watchers at Canopy Camp, which is a setup for birders. Before dawn, we traveled by car, river boat, and hiking through banana fields and forest to see the magnificent eagles.

Few people ever see these raptors, whose terrain is mainly limited to the Darién Gap.

Harpy Eagles are the world’s second-largest eagles and are strong enough to hunt small monkeys. They can live for sixty years and have a single chick only every second year.

The nest was on private farmland, next to the park. In Darién, the line between forest and agriculture is blurred. Abandoned rice fields have returned to wetlands. Bananas grow wild in secondary forests, land cleared long ago for cattle retains some large trees. There are a few productive uses for the soft wood of the giant Cuipo trees (Cavanillesia platanifolia). They were often left to grow old without being covered in vines, providing shade for cattle and nests for birds. Fences are made by growing trees along borders, rather than dead wood.

(Image- Left: Harpy Chick, Right: Harpy Eagle)

The biodiversity is incredible. With the help of an experienced bird guide, we saw around 200 of the 1030 bird species in Panama, a small country of four million people, with three million living in rural areas. While biodiversity is linked to rainforests, the surrounding areas provide good habitat for many species and good opportunities for birdwatching.

Birders are people who go out of their way to see birds. It’s their hobby and often their life passion. They take meticulous records of sightings (and soundings), uploading them to [eBird] or [ iNaturalist]. This makes great data for data scientists. While some are only interested in seeing or photographing birds, others have an interest in conservation, ecology, biology, or even lepidoptery.

As someone who spends more time working at landscape scales with satellite imagery, I was left thinking about the biodiversity value of agricultural land close to protected areas. These buffer zones can be managed in ways that are productive for the people whose livelihoods depend on the crops, while also providing some habitat for the species that spill out of the forest. Even providing migration corridors for some species to reach other forest reserves can improve the diversity of the gene pool.

More than 45% of Panama is still forested. Over fifty protected areas cover 30% of the country. The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute was founded in Panama in 1910. Studies led to the protection of more than 54% of Panama’s marine areas.

The Darién tropical moist forest was fully protected by 1980.

Darién is also one of the provinces with the most registered cattle in Panama.

Cattle ranching is a good business in the short term, but the losses to nature and the country are very large with the old model of extensive cattle ranching. Many ranchers have begun to apply silvopastoral systems, which maintain trees, use living fences, and better pastures as a more sustainable alternative. It varies a lot between farms.

Panama has 2,300 species of trees – more than twice the number found in all of North America. The great majority grows in the rain forest, surrounded by palms, vines and ferns, fungi, insects, birds, and mammals.

The remaining forest is the main source of all this biodiversity, and protected reserves must be retained but expanding them or even managing them is politically challenging. Promoting biodiversity in surrounding agricultural areas may be an easier goal. The COP28 30×30 Biodiversity Goals may accelerate finance and education to increase protected areas and support sustainable practices in the buffer zones.

Teak plantations are everywhere, and I could see little bird life or biodiversity in any of these plantations. Teak is native to Southeast Asia but is now cultivated here. Perhaps these plantations reduce the depletion of native teak in Myanmar. The plantations lack the complex multi-storied canopy and diversity of habitat found in primary forests.

In Panama, more than 500 species are threatened with extinction, mostly from human activities like razing forests and wetlands to build farms and cities.

Many species are illustrated in the stunning Panama Biodiversity Museum, where colour cards for each species show their [conservation status] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conservation_status); greens for Not-Threatened to Near Threatened; yellow for Vulnerable;, orange for Endangered; and red for Critically Endangered. Black is for extinct species. Gray cards illustrate threats such as hunting, habitat degradation, and loss. The museum designed by American architect Frank Gehry [1929-2025] is built on a causeway built from tailings excavated to dredge the Panama Canal. It’s top class.

New roads often promote deforestation by making it easier to move timber, cattle, and crops to market. The construction of new roads to Darién in the 1980s increased deforestation in the area. Even birders find it impenetrable.

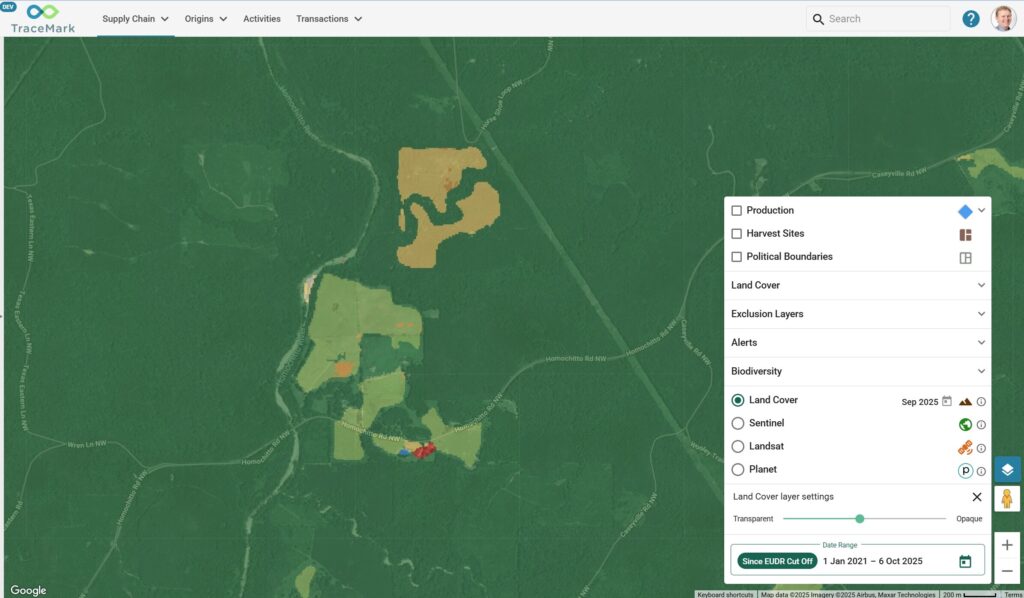

Recently, we augmented our TraceMarkTM platform with Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) and the Science Based Targets Network (SBTN) focused metrics, to allow users to understand the risk scores and impact scores for a set of ecosystem service categories such as land use change; vegetation and ecosystem health; water availability and quality; biodiversity and habitat integrity; extreme weather events; and soil productivity. These scores allow comparisons across categories and across sites to provide a quick, visual dashboard of which categories need mitigation actions. Click here to learn more.

By Chris Goodman, Senior Google Cloud Engineer, NGIS

Related Articles

Here are more related articles you may be interested in.